John Miller, man without a country

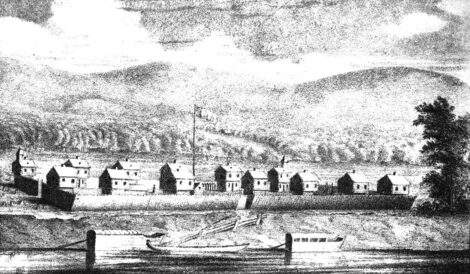

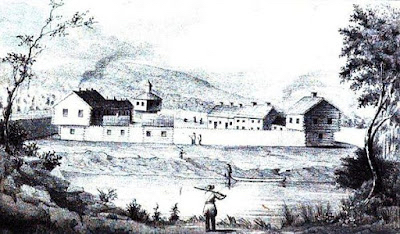

- (Image from Samuel Hildreth’s Pioneer History) Fort Frye circa 1791.

(Image from Samuel Hildreth’s Pioneer History) Fort Frye circa 1791.

John Miller was bound and left in camp by a Delaware Indian war party. They were headed for Waterford to attack settlers at Fort Frye in March of 1791. John had to warn his friends at Waterford. He had lived with them in the summer of 1790, using his hunting skills to supply wild game for the fledgling settlement.

Miller was a “Stockbridge Indian” from Massachusetts who had come to Marietta in 1788 with General James Mitchell Varnum. He had lived most of his life among white people and was less attached to his native heritage. John and George Morgan White Eyes (son of chief White Eyes) were friends at Princeton University in the 1780’s. A chance meeting between the two in 1790 at Fort Harmar rekindled their friendship. George hired John as a guide and hunter. But after several months with George and his Delaware tribe at Sandusky, John longed to rejoin his friends at Waterford.

The Delaware war party headed to southeast Ohio from Sandusky. John Miller tagged along so he could return to the area, knowing he’d have to find a way out. They camped near present day Duncan Falls on the Muskingum River. John was alarmed; he realized they planned to attack Waterford settlers soon. John had to think fast: how could he stay behind without raising suspicion? He deliberately cut his foot while chopping wood, pretending it was accidental. They left him in camp but tied him up, uncertain of his true intentions.

John watched and listened after the Delaware war party left camp on that cold March morning. A few birds chirped in the mist; deer wandered through the camp. Otherwise, it was still. Were they gone? Yes. He struggled to free himself. His mind was racing. How could he get to Waterford before the war party attacked? He watched the Muskingum River flow by, swollen by heavy rains. That was it! He would have to take his chances floating down the dangerously swift water. By late afternoon he worked himself free. He scrambled to retrieve logs and grapevines to build a raft. At dusk he set off, his foot throbbing. Darkness enveloped him; now he was at the mercy of the river.

At daybreak, John Miller was chilled through from a night on the water. He panicked as he spotted a campfire. It was the war party. He jerked as rifle fire echoed in the hills. Fortunately, they were hunting and not firing at him. He clung prostrate to the raft, heart pounding, but skimmed past without being seen.

He landed just above Fort Frye and cautiously approached the fort. He was dressed like an Indian but spoke good English and named people in the fort who knew him. They let him in – at gun point. Some didn’t believe his warning and thought he was a spy for the Indians. Fortunately, the commander, Captain William Gray, did believe him. John gave him full details of the Indians’ plan. The settlers at Fort Frye went on full alert, working feverishly to secure the fort. Indians did finally attack after a few days and were repulsed. Miller’s warning saved many lives.

John Miller was now in a difficult spot – like a man without a country. The Delaware Indians would torture and kill him if caught. And some of the white settlers distrusted him. He was dismayed by his predicament – and afraid. How could he be distrusted by the Indians and whites when he had friends in both groups? Yet so it was. John Miller fled to Marietta and returned to New England. His experiment at living in the Ohio Country was over.