Kidnapped!

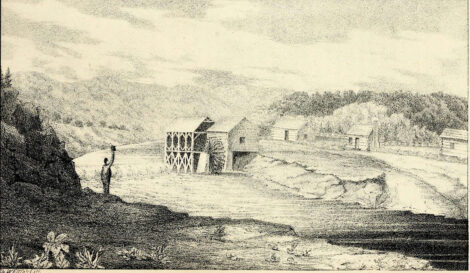

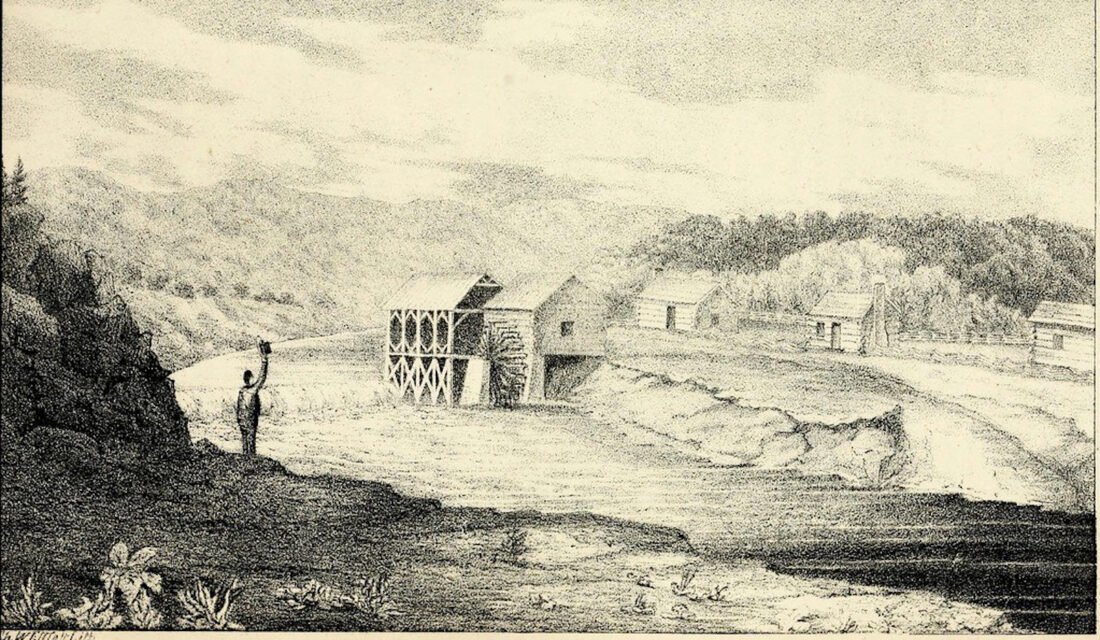

- (Photo provided by Historical Collections of Ohio by Henry Howe, 1886) Wolf Creek Mill, the first mill in the Ohio country, constructed along Wolf Creek in 1789.

(Photo provided by Historical Collections of Ohio by Henry Howe, 1886) Wolf Creek Mill, the first mill in the Ohio country, constructed along Wolf Creek in 1789.

Early Marietta

By David Baker

“How could I have been so stupid!” John Gardner growled to himself as disbelief then fear gripped him. He was led away with a noose around his neck by several Indians and a white man. In September of 1789, John Gardner and Jervis Cutler were helping each other clear their lots on the fertile peninsula at Waterford (originally called Plainfield). Jervis left for Marietta to get supplies. John took a break, sitting on a stump, totally absorbed counting his musket balls. Several Indians and a white man moved in without his noticing. He looked up, surprised but not alarmed. The white guy beckoned to him. Indians were not a threat, John thought, since friendly Delawares hunted in the area. He was wrong. The white man grabbed his gun and instantly he was restrained and led away by the Indians.

Young John Gardner was a native of Marblehead, Mass., and was one of the original 48 pioneers who landed at Marietta in 1788. He was ready for adventure … but not this kind. Indian attacks were becoming more common as they resisted white incursion into their lands. White settlers fought back. The so-called Northwest Indian War became a vicious cycle of raids by one group, retribution by the other, with occasional attempts at peace. Most settlers knew that they needed a guard or sentry when in the open. In the previous spring, Captain Zebulun King had been killed and scalped as he farmed in Belpre. And two boys had been killed in August, 1789 at Neal’s station in neighboring Virginia.

He compulsively relived the events that led to his capture. Why had he been so lax and unaware of his surroundings? As they walked, a breeze carried the familiar voices of men working nearby. Later he could see workers within earshot at the mills under construction on Wolf Run. But breaking silence meant sudden death. He thought of his family back in Massachusetts who questioned his wish to live on the frontier. Maybe he should have gone to sea, following his family’s maritime traditions.

They stopped and set up camp, many miles southwest of Waterford on Federal Creek. That night he was bound laying down with leather thongs to a stout sapling bent over to the ground. Cow bells were attached to the sapling which would alert Indians if he tried to escape. He slept fitfully. The next day, they asked him if he could build cabins. Yes, he said, he was expert at that. They offered him a young squaw if he agreed to stay with them. Later the Indians cut his hair and painted his face, hoping to acclimate him to Indian life. No way, Gardner vowed to himself.

The second night, he was bound as before. A light rain fell. That helped loosen the leather ties. He freed himself of those. Then in agonizing slow motion, he gradually, “fearfully,” released himself from the sapling without ringing any of the bells. Free! But he wasn’t done: he boldly tiptoed over and picked up his musket lying inches from a sleeping Indian. He then escaped, walked or ran, stopping only for water. He slept that night in a log and reached Waterford the next day. I wonder how he navigated through complete wilderness without significant landmarks for at least 20 miles to get home.

Remember Jervis Cutler who was helping John clear land? They were reunited just as Jervis returned from Marietta, unaware of John Gardner’s four-day ordeal. The next day they were again clearing land, but much more vigilant. John Gardner was lucky to survive; hundreds of others were not so fortunate. It took courage and perseverance to survive the first few years in Washington County.