Murder of Jima Ann Dotson: Sensational murder case reaches 50th anniversary

Sensational murder case reaches 50th anniversary

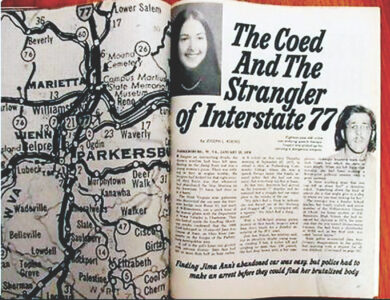

- (Photo Provided) A story about Jima Ann Dotson in the 1976 issue of “Inside Detective.” Dotson was abducted and murdered by John Calvin Bayles, who was convicted in the case and died in prison.

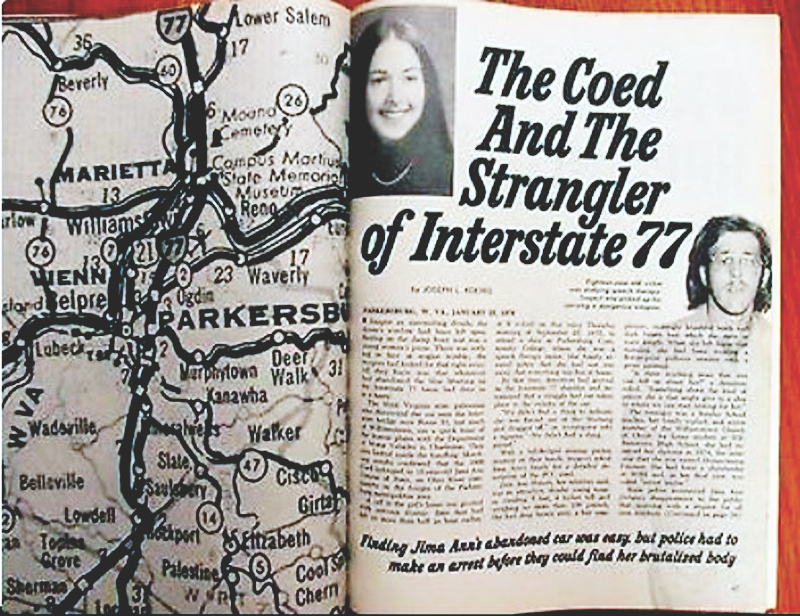

- (Photo Provided) Jima Ann Dotson in her high school portrait.

(Photo Provided) A story about Jima Ann Dotson in the 1976 issue of “Inside Detective.” Dotson was abducted and murdered by John Calvin Bayles, who was convicted in the case and died in prison.

PARKERSBURG — Fifty years have passed since the sensational and notorious murder of Jima Ann Dotson in Wood County.

Dotson, 18, who graduated from Williamstown High School several months before, on Sept. 25, 1972, was driving to class at Parkersburg Community College, now West Virginia University at Parkersburg. She never returned home.

She was missing for 17 days before she was found in a grave in Belpre near a race track and John Calvin Bayles was charged with her murder.

Prior to her discovery, several searches involving about 600 residents working with State Police and local agencies were conducted along Interstate 77, the direct way to Staunton Avenue and the college from Boaz.

“There were hundreds of people who looked for her,” said Bob Newell, a retired police chief who has written several books about the most infamous crimes in the region.

(Photo Provided) Jima Ann Dotson in her high school portrait.

Searches for her had produced only bloody clothing, said Carrie Luthringer, Dotson’s first cousin and one of the few surviving members of the family in the area. Luthringer was 11 years old at the time.

“I remember my mom crying,” she said.

Dotson’s abandoned car, a Ford Mustang, was found by the State Police on the interstate not far from an I-77 entrance ramp. No signs of a struggle were found and her purse, books, car keys and other personal items were inside the vehicle.

Luthringer learned about her cousin from a story in the newspaper.

“My mom said she was missing,” Luthringer said.

She remembers all the details of the 17 days Dotson was missing before her body was found, a time that felt like years, Luthringer said.

The case started when Dotson was stopped in her car by her assailant who forced her into his car. While driving on I-77, people saw Dotson fighting to get out of the car, but didn’t stop because they thought it was two people in a spat, Luthringer said. The man killed the former cheerleader in his car.

“The culture was different back in 1975,” she said. “People didn’t want to get involved. They thought it was a lovers’ quarrel.”

The investigation led authorities to Belpre where Dotson was found in a grave on land owned by the suspect’s family. A neighbor and Jim Dotson, Dotson’s father, went to identify the body.

Her father was unable to go inside the room where the body was kept, so the neighbor identified Dotson, Luthringer said.

Dotson was severely beaten in the head, Luthringer said.

“She was unrecognizable,” Luthringer said,

Jim died May 1, 2002, at the age of 71. Dotson’s mother, Donna, died on May 16, 2023, at the age of 93.

The incident has affected Lutringer all these years and she thinks about her cousin every day. Luthringer, a nurse, said she made career decisions based on her cousin’s murder, such as working in a psychiatric ward. The incident has given her a better insight into interactions with patients.

“It has affected my life so much,” she said.

As a young woman, Luthringer became wary of the streets she walked when going home. She was careful where she parked and kept her keys with her at all times.

“Wherever I walked, I had my keys in my hand always ready for anything,” she said.

Luthringer married, but had no children, wanting to never go through the pain her parents and family went through over Dotson’s murder. The murder devastated her mother and aunt, Luthringer said.

“That’s the reason why I didn’t have children,” she said. “I don’t think I could ever go through anything like that.”

Talking about the case now, the 50th anniversary, is therapeutic, according to Luthringer. She’s trying to get everything behind her.

“That’s why I’m talking about this now,” Luthringer said.

The murder led to an unofficial law that police won’t stop someone in dark places.

The incident changed how women took precautions for their safety, Newell said. The history should be a reminder for today, he said.

“Back then it gave a heightened awareness to women,” Newell said. “Hopefully, this will put this in their minds again.”

Newell has written books about crime in the Mid-Ohio Valley. The Dotson story will be included in the soon to be published “Violence in the Valley 2: Coroners’ Reports.”

A missing persons investigation immediately began because of the unusual circumstances of the disappearance, Newell said. Investigators first believed Dotson voluntarily got into another car, he said.

The late Sgt. Russ Miller, a retired State Police trooper and former Parkersburg Police chief who investigated the murder, said he originally believed someone pulled alongside of her and may have motioned something was wrong with her cars or tires, Newell said.

Boyfriends, ex-boyfriends and her lifestyle ended without any leads to follow, Newell said.

“She studied hard, was popular with school mates, had no enemies and didn’t frequent bars or night clubs,” Newell wrote in a story for his next book. “Jima was a low-risk victim for any crime to have been committed against her.”

A theory was someone posing as a police officer with a blue light in his car stopped Dotson, Newell said. Police were advised to avoid stopping cars, he said.

One of the searches was led by Trooper T.K. Williams, who was in the same State Police Academy class as Newell, in Waverly. Newell and his wife, Debbie, participated in that search.

Several days later came the first break, Newell said. Dotson’s personal items were found in Waverly near Corbitt Hill Road, including her shoes, he said.

With the probability that Dotson was dead, the search was concentrated in the Waverly area, Newell said. Nothing was found, he said.

News was spreading throughout the county, Newell said. Woodrow Ruckman, a farmer in Waverly, recollected on the day Dotson became missing, a young man parked on a nearby narrow road and his tires sunk into the soft mud, Newell said.

Ruckman, who was flagged down while he was driving his tractor, pulled the car out of the mud, Newell said. The youth said he didn’t have any money on him, but promised to return with $10, Newell said.

Ruckman, who didn’t believe the man would return, wrote the license number, address and phone number of the driver. After a couple days, Ruckman called the number and spoke to a lady about his money for the tow, Newell said.

Ruckman threatened to call the police if he wasn’t paid, Newell said. The young driver was there the next day with a check for $10 from his mother, Newell said.

State Police also checked the license number and the plate was registered to John Calvin Bayles, Newell said.

Ruckman showed investigators where the car was stuck, a location at the wood line where Dotson’s shoes and clothing were found, Newell said. Bayles was now a suspect, Newell said.

Bayles had been arrested by Parkersburg Police several months earlier and was accused of attempting to commit the same act twice before in Parkersburg, Newell said.

Bayles was arrested in 1974 after an incident in the parking lot of the former Montgomery Wards on Murdoch Avenue where, wielding a hunting knife, opened the door to a car with a woman and young son, Newell said. The woman screamed and Bayles ran away to his car and fled the area, Newell said.

Bayles and his car were later seen by police officers who arrested and charged him with carrying a deadly weapon, a misdemeanor, Newell said. Bayles was convicted in magistrate court, but an appeal ended in a hung jury in circuit court.

Several rapes had been reported in the downtown area around the same time, Newell said.

Police put a patrol car where key punch operators got off work early in the morning at Public Debt.

After Montgomery Wards, Bayles attempted to abduct a woman who worked at Public Debt in the early morning of Sept. 17, 1974, Newell said. He followed her in his car, flashed his lights and she stopped thinking it was someone she knew and rolled the window down just enough for him to reach inside and unlock the door, Newell said. Bayles held a knife to her throat and told her to move over on the seat, Newell said.

However, the passenger door of the car was unlocked and she managed to escape from the moving vehicle, Newell said. The man was later identified as Bayles, Newell said.

Bayles abandoned her car near where he had left his own vehicle, then fled town, Newell said.

State police began an around-the-clock surveillance of Bayles, the most probable suspect, and hoped he would go to where Dotson was buried, Newell said.

Bayles on Oct. 11, 1975, was at the River City night club near Vienna where he left without a victim, Newell said. He was stopped by troopers for a traffic violation, a broken license plate light, a citation that came with up to 15 days in jail, Newell said. It was an offense that allowed State Police to take him into custody, but the constitutionality of the stop was appealed over the next three decades, Newell said.

Officers found a crossbow in the car, which was prohibited to possess before they were legalized, Newell said.

Bayles was taken to the State Police barracks on W.Va. 47 where he confessed to killing Dotson and told investigators where she was buried, Newell said.

“At one point he reportedly fell on his knees grabbing Sgt. Miller’s leg while exclaiming he was an ‘animal and didn’t deserve to live any longer,'” Newell wrote in his book.

Bayles was convicted of first-degree murder in 1976 and sentenced by Judge Donald F. Black to life without parole. Bayles died in prison on Dec. 2, 2022, at the age of 71.