Nature carries on

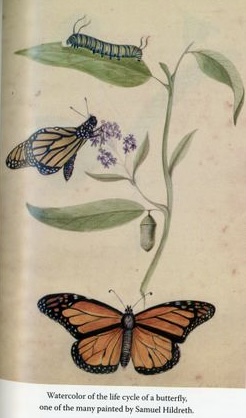

- (Illustrations by Samuel Hildreth) Life cycle of a butterfly.

- Scan this code to learn more about doctor, historian, and scientist Samuel Hildreth.

(Illustrations by Samuel Hildreth) Life cycle of a butterfly.

Much has changed from early pioneer days, one thing changes little: nature. Summer gives us nature in full force. August nights in the woods start at dusk with lightning bugs, birds singing, and the plaintive buzzing of seasonal cicadas. After dark there is a din of whirring crickets, dissonant quacking of tree frogs, and wheezy katydids. Recently it dawned on me – settlers two centuries ago saw and heard the same things.

Meriwether Lewis at the beginning of the Lewis and Clark Expedition floated down the Ohio River. His journal in September 1803: “observed a number of squirrels swiming the Ohio River…” Squirrels migrated then – millions of them. Lewis’s dog Seaman recovered several squirrels, “I thought them when fryed a pleasent food.” On September 13 Lewis stopped at Marietta. There he “… observed many passenger pigeons…”. Now extinct, their huge flocks often blocked the sun.

What’s warm weather without bugs? Col. John May was “tormented beyond measure by myriads of gnats. They not only bite surprisingly but get down one’s throat.” Bugs (Ok, insects) could be dangerous. Mosquitoes bore diseases, such as malaria. Many were the poignant cases of sickness and death. Civic leader Ephraim Cutler travelled from New England to Marietta in 1795. On the journey two of their children died of illness. Cutler himself was bedridden on arriving here. Several times, including 1822 and 1823, there were epidemics that infected hundreds. In late 1822, 95 people died in Marietta, which then had a population of 2,000.

The buzzing periodic cicadas have been around for millenia; the first visit locally was 1795. Their scientific name is magicicada septendecim, attesting in Latin to its “magical” reappearance every 17 years. Scientist and historian Samuel Hildreth was one of the first in the country to observe the cycle, write about it, and draw illustrations.

The rivers offered needed water for settlers and for transportation – but were fickle. Thomas Walcutt in February 1790: “Rivers choked with ice, which stopped all river traffic.” A week later, “At sunrise water rising fast…before we could get our breakfast done, water came in so fast that the floor was afloat…” With no locks and dams, rivers had shallows, deep pools, riffles, and slack water. One could wade across during dry spells and walk over them when frozen.

Scan this code to learn more about doctor, historian, and scientist Samuel Hildreth.

Rivers provided food. In 1790 James Patterson caught a 96 lb catfish. He had set out a trotline, then anchored his canoe and slept. The fish hooked itself and managed to drag the anchored canoe into deep water near an island – where Patterson found himself upon waking. Meriwether Lewis saw “a great number of Fish of different kinds, the Stergeon, Bass, Cat fish, pike.” Walcutt marveled at another water critter, a crayfish: “a complete lobster in miniature about two inches in length…found in streams and springs.”

The area teemed with plant life. Towering trees provided needed lumber for construction, but their shade hindered growth of crops. One of today’s nuisance plants also bedeviled settlers; Colonel John May reported “feeling the (unpleasant) effects of poison ivy” after clearing land. Plants also were a food source. Ever heard of nettle, celandine, and purslane? They helped settlers survive periods of famine early on. Historian Samuel Hildreth: “(the) tender tops (of nettle) were palatable and nutritious. The young, juicy plants of celandine afforded also a… pleasant dish.” Hildreth, also a scientist, was awed by this plant life. He observed that purslane grew “as if by magic” when exposed to sunlight from “seeds scattered ages before, by the Creator of all things.”

Mark your calendar: the periodic cicadas will return here in 2033. The cycle of God’s creation goes on.